I recently ran across a comparison of React.js to Vue.js for rendering dynamic tabular data, and I got curious to see how Reagent would stack up against them.

The benchmark simulates a view of football games represented by a table. Each row in the table represents the state of a particular game. The game states are updated once a second triggering UI repaints.

I structured the application similarly to the way that React.js version was structured in the original benchmark. The application has a football.data namespace to handle the business logic, and a football.core namespace to render the view.

Implementing the Business Logic

Let's start by implementing the business logic in the football.data namespace. First, we'll need to provide a container to hold the state of the games. To do that we'll create a Reagent atom called games:

(ns football.data

(:require [reagent.core :as reagent]))

(defonce games (reagent/atom nil))

Next, we'll add a function to generate the fake players:

(defn generate-fake-player []

{:name (-> js/faker .-name (.findName))

:effort-level (rand-int 10)

:invited-next-week? (> (rand) 0.5)})

You can see that we're using JavaScript interop to leverage the Faker.js library for generating the player names. One nice aspect of working with ClojureScript is that JavaScript interop tends to be seamless as seen in the code above.

Now that we have a way to generate the players, let's add a function to generate fake games:

(defn generate-fake-game []

{:id (-> js/faker .-random (.uuid))

:clock 0

:score {:home 0 :away 0}

:teams {:home (-> js/faker .-address (.city))

:away (-> js/faker .-address (.city))}

:outrageous-tackles 0

:cards {:yellow 0 :read 0}

:players (mapv generate-fake-player (range 4))})

With the functions to generate the players and the games in place, we'll now add a function to generate a set of initial game states:

(defn generate-games [game-count]

(reset! games (mapv generate-fake-game (range game-count))))

The next step is to write the functions to update the games and players to simulate the progression of the games. This code translates pretty much directly from the JavaScript version:

(defn maybe-update [game prob path f]

(if (< (rand-int 100) prob)

(update-in game path f)

game))

(defn update-rand-player [game idx]

(-> game

(assoc-in [:players idx :effort-level] (rand-int 10))

(assoc-in [:players idx :invited-next-week?] (> (rand) 0.5))))

(defn update-game [game]

(-> game

(update :clock inc)

(maybe-update 5 [:score :home] inc)

(maybe-update 5 [:score :away] inc)

(maybe-update 8 [:cards :yellow] inc)

(maybe-update 2 [:cards :red] inc)

(maybe-update 10 [:outrageous-tackles] inc)

(update-rand-player (rand-int 4))))

The last thing we need to do is to add the functions to update the game states at a specified interval. The original code uses Rx.js to accomplish this, but it's just as easy to do using the setTimeout function with Reagent:

(defn update-game-at-interval [interval idx]

(swap! games update idx update-game)

(js/setTimeout update-game-at-interval interval interval idx))

(def event-interval 1000)

(defn update-games [game-count]

(dotimes [i game-count]

(swap! games update i update-game)

(js/setTimeout #(update-game-at-interval event-interval i)

(* i event-interval))))

The update-games function updates the state of each game, then sets up a timeout for the recurring updates using the update-game-at-interval function.

Implementing the View

We're now ready to write the view portion of the application. We'll start by referencing the football.data namespace in the football.core namespace:

(ns football.core

(:require

[football.data :as data]

[reagent.core :as reagent]))

Next, we'll write the components to display the players and the games:

(defn player-component [{:keys [name invited-next-week? effort-level]}]

[:td

[:div.player

[:p.player__name

[:span name]

[:span.u-small (if invited-next-week? "Doing well" "Not coming again")]]

[:div {:class-name (str "player__effort "

(if (< effort-level 5)

"player__effort--low"

"player__effort--high"))}]]])

(defn game-component [game]

[:tr

[:td.u-center (:clock game)]

[:td.u-center (-> game :score :home) "-" (-> game :score :away)]

[:td.cell--teams (-> game :teams :home) "-" (-> game :teams :away)]

[:td.u-center (:outrageous-tackles game)]

[:td

[:div.cards

[:div.cards__card.cards__card--yellow (-> game :cards :yellow)]

[:div.cards__card.cards__card--red (-> game :cards :red)]]]

(for [player (:players game)]

^{:key player}

[player-component player])])

(defn games-component []

[:tbody

(for [game @data/games]

^{:key game}

[game-component game])])

(defn games-table-component []

[:table

[:thead

[:tr

[:th {:width "50px"} "Clock"]

[:th {:width "50px"} "Score"]

[:th {:width "200px"} "Teams"]

[:th "Outrageous Tackles"]

[:th {:width "100px"} "Cards"]

[:th {:width "100px"} "Players"]

[:th {:width "100px"} ""]

[:th {:width "100px"} ""]

[:th {:width "100px"} ""]

[:th {:width "100px"} ""]]]

[games-component]])

You can see that HTML elements in Reagent components are represented using Clojure vectors and maps. Since s-expressions cleanly map to HTML, there's no need to use an additional DSL for that. You'll also notice that components can be nested within one another same way as plain HTML elements.

Noe thing to note is that the games-component dereferences the data/games atom using the @ notation. Dereferencing simply means that we'd like to view the current state of a mutable variable.

Reagent atoms are reactive, and listeners are created when the atoms are dereferenced. Whenever the state of the atom changes, any components that are observing the atom will be notified of the change.

In our case, changes in the state of the games atom will trigger the games-component function to be evaluated. The function will pass the current state of the games down to its child components, and this will trigger any necessary repaints in the UI.

Finally, we have a bit of code to create the root component represented by the home-page function, and initialize the application:

(defn home-page []

[games-table-component])

(defn mount-root []

(reagent/render [home-page] (.getElementById js/document "app")))

(def game-count 50)

(defn init! []

(data/generate-games game-count)

(data/update-games game-count)

(mount-root))

We now have a naive implementation of the benchmark using Reagent. The entire project is available on GitHub. Next, let's take a look at how it performs.

Profiling with Chrome

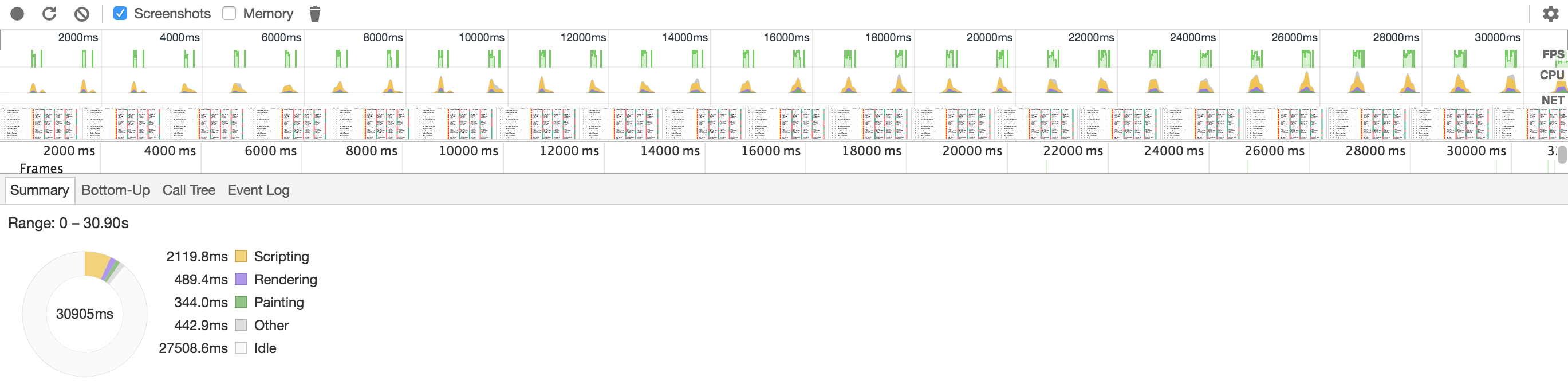

When we profile the app in Chrome, we'll see the following results:

Here are the results for React.js and Vue.js running in the same environment for comparison:

As you can see, the naive Reagent version spends about double the time scripting compared to React.js, and about four times as long rendering.

The reason is that we're dereferencing the games atom at top level. This forces the top level component to be reevaluated whenever the sate of any game changes.

Reagent provides a mechanism for dealing with this problem in the form of cursors. A cursor allows subscribing to changes at a specified path within the atom. A component that dereferences a cursor will only be updated when the data the cursor points to changes. This allows us to granularly control what components will be repainted when a particular piece of data changes in the games atom. Let's update the view logic as follows:

(defn player-component [player]

[:td

[:div.player

[:p.player__name

[:span (:name @player)]

[:span.u-small

(if (:invited-next-week? @player)

"Doing well" "Not coming again")]]

[:div {:class-name (str "player__effort "

(if (< (:effort-level @player) 5)

"player__effort--low"

"player__effort--high"))}]]])

(defn game-component [game]

[:tr

[:td.u-center (:clock @game)]

[:td.u-center (-> @game :score :home) "-" (-> @game :score :away)]

[:td.cell--teams (-> @game :teams :home) "-" (-> @game :teams :away)]

[:td.u-center (:outrageous-tackles @game)]

[:td

[:div.cards

[:div.cards__card.cards__card--yellow (-> @game :cards :yellow)]

[:div.cards__card.cards__card--red (-> @game :cards :red)]]]

(for [idx (range (count (:players @game)))]

^{:key idx}

[player-component (reagent/cursor game [:players idx])])])

(def game-count 50)

(defn games-component []

[:tbody

(for [idx (range game-count)]

^{:key idx}

[game-component (reagent/cursor data/games [idx])])])

(defn games-table-component []

[:table

[:thead

[:tr

[:th {:width "50px"} "Clock"]

[:th {:width "50px"} "Score"]

[:th {:width "200px"} "Teams"]

[:th "Outrageous Tackles"]

[:th {:width "100px"} "Cards"]

[:th {:width "100px"} "Players"]

[:th {:width "100px"} ""]

[:th {:width "100px"} ""]

[:th {:width "100px"} ""]

[:th {:width "100px"} ""]]]

[games-component]])

(defn home-page []

[games-table-component])

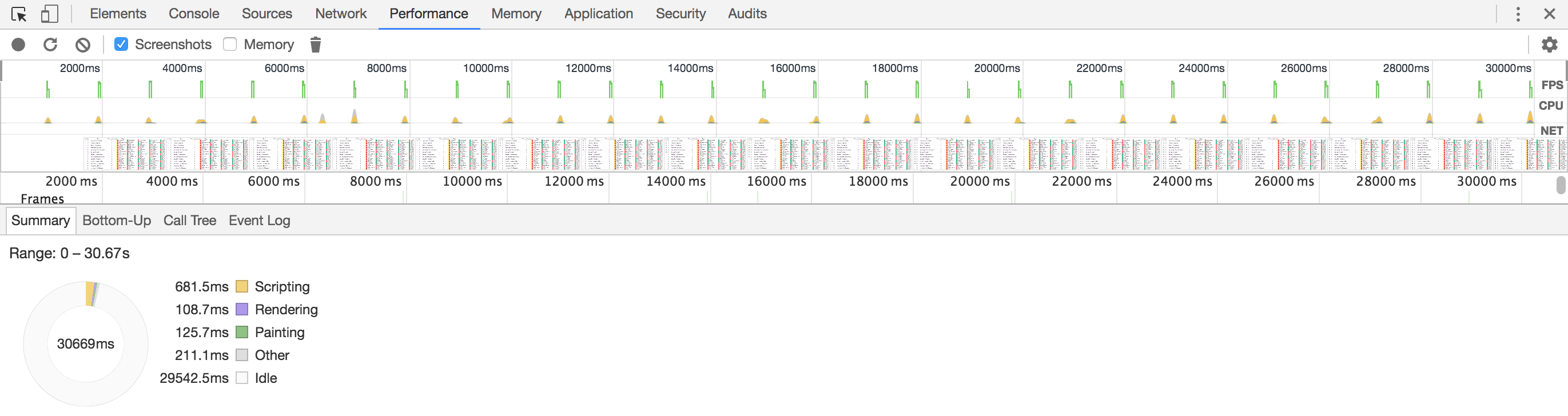

The above version creates a cursor for each game in the games-components. The game-component in turn creates a cursor for each player. This way only the components that actually need updating end up being rendered as the state of the games is updated. Let's profile the application again to see how much impact this has on its performance:

The performance of the Reagent code using cursors now looks similar to that of the Vue.js implementation. You can see the entire source for the updated version here.

Conclusion

In this post we saw that ClojureScript with Reagent provides a compelling alternative to JavaScript offerings such as React.js and Vue.js.

Reagent allows writing succinct solutions that perform as well as those implemented using native JavaScript libraries. It also provides us with tools to intuitively reason about what parts of the view are going to be updated.

Likewise, we get many benefits by simply switching from using JavaScript to ClojureScript.

For example, We already saw that we didn't need any additional syntax, such as JSX, to represent HTML elements. Since HTML templates are represented using regular data structures, they follows the same rules as any other code. This allows us to transform them just like we would any other data in our project.

In general, I find ClojureScript to be much more consistent and less noisy than equivalent JavaScript code. Consider the implementation of the updateGame function in the original JavaScript version:

function updateGame(game) {

game = game.update("clock", (sec) => sec + 1);

game = maybeUpdate(5, game, () => game.updateIn(["score", "home"], (s) => s + 1));

game = maybeUpdate(5, game, () => game.updateIn(["score", "away"], (s) => s + 1));

game = maybeUpdate(8, game, () => game.updateIn(["cards", "yellow"], (s) => s + 1));

game = maybeUpdate(2, game, () => game.updateIn(["cards", "red"], (s) => s + 1));

game = maybeUpdate(10, game, () => game.update("outrageousTackles", (t) => t + 1));

const randomPlayerIndex = randomNum(0, 4);

const effortLevel = randomNum();

const invitedNextWeek = faker.random.boolean();

game = game.updateIn(["players", randomPlayerIndex], (player) => {

return player.set("effortLevel", effortLevel).set("invitedNextWeek", invitedNextWeek);

});

return game;

}

Compare it with the equivalent ClojureScript code:

(defn update-rand-player [game idx]

(-> game

(assoc-in [:players idx :effort-level] (rand-int 10))

(assoc-in [:players idx :invited-next-week?] (> (rand) 0.5))))

(defn update-game [game]

(-> game

(update :clock inc)

(maybe-update 5 [:score :home] inc)

(maybe-update 5 [:score :away] inc)

(maybe-update 8 [:cards :yellow] inc)

(maybe-update 2 [:cards :red] inc)

(maybe-update 10 [:outrageous-tackles] inc)

(update-rand-player (rand-int 4))))

ClojureScript version has a lot less syntactic noise, and I find this has direct impact on my ability to reason about the code. The more quirks there are, the more likely I am to misread the intent. Noisy syntax results in situations where code looks like it's doing one thing, while it's actually doing something subtly different.

Another advantage is that ClojureScript is backed by immutable data structures by default. My experience is that immutability is crucial for writing large maintainable projects, as it allows safely reasoning about parts of the code in isolation.

Since immutability is pervasive as opposed to opt-in, it allows for tooling to be designed with it in mind. For example, Figwheel plugin relies on this property to provide live hot reloading in the browser.

Finally, ClojureScript compiler can do many optimizations, such as dead code elimination, that are difficult to do with JavaScript. I highly recommend the Now What? talk by David Nolen that goes into more details regarding this.

Overall, I'm pleased to see that ClojureScript and Reagent perform so well when stacked up against native JavaScript libraries. It's hard to overstate the fact that a ClojureScript library built on top of React.js can outperform React.js itself.