Grounding LLMs with Recursive Code Execution

Despite context windows expanding to millions of tokens, LLMs still struggle with the fundamental task of precision. When you ask an LLM to "analyze this report," it often glances at the text and simply hallucinates a plausible-sounding answer based on probability.

A good example of the problem can be seen when asking a model to sum sales figures from a financial report. Left to its own devices, it will likely not bother reading the whole document and simply give you a made-up answer. This is especially a problem with smaller models that you can run locally.

The standard approach to dealing with this problem is to use Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), which relies on semantic similarity (embeddings). If you ask for "sales figures," a Vector DB retrieves chunks of text that sound like sales figures. However, semantic similarity is fuzzy and limited in functionality. Embeddings can't count, so you can't ask questions like "count the number of times X happens." They also can't handle information scattered across a bunch of unrelated lines in a document. Furthermore, they don't distinguish between concepts like "Projected Sales" and "Actual Sales" when they appear in similar contexts.

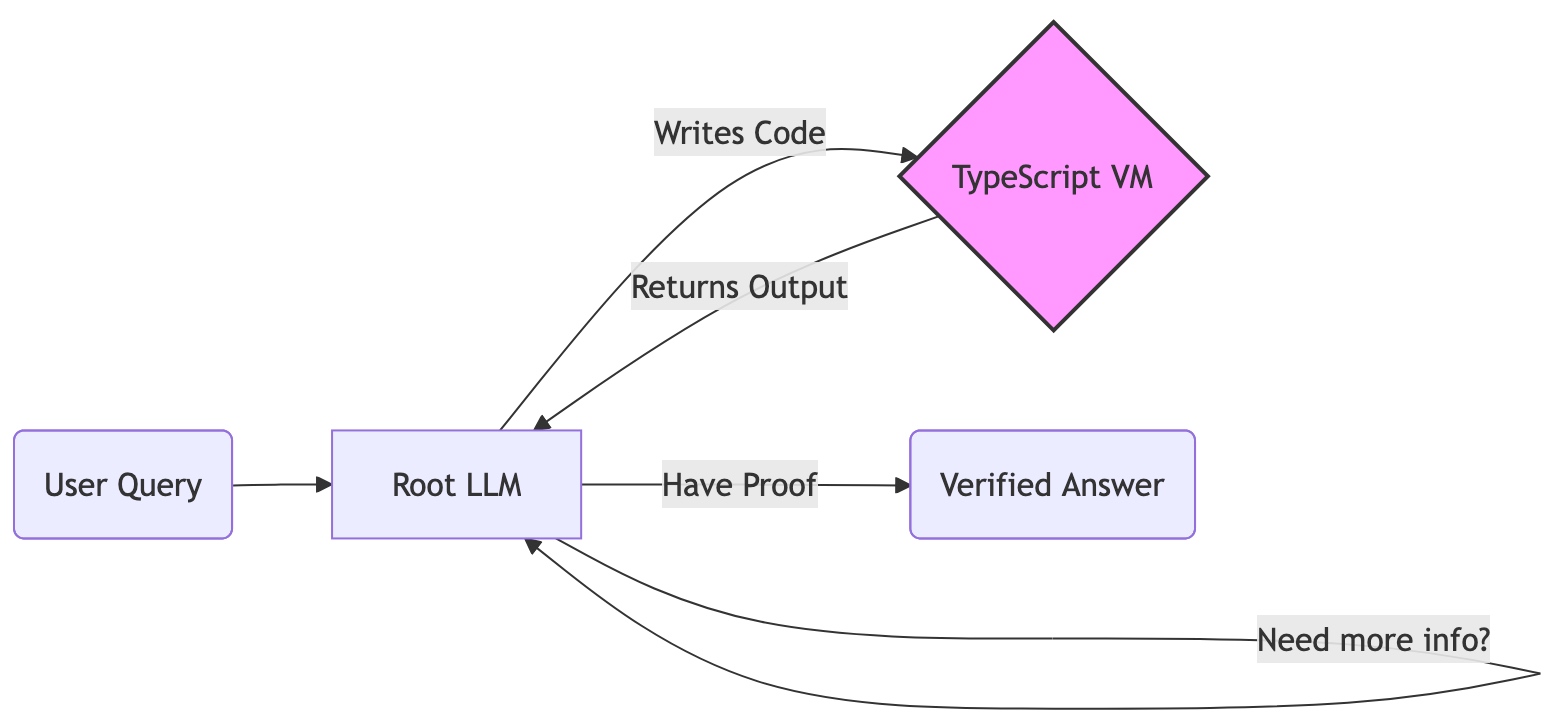

It would be nice to have a system that treats text as a dataset to be queried rather than a prompt to be completed. This is where the Recursive Language Model paper comes in. The core idea here is that instead of having the model operate directly on the document, it uses a programmatic interface to interact with it via a REPL. The model acts as a programmer writing code to explore the document, interpreting execution results, and only then formulating an answer based on them.

The core insight is that code execution provides grounding for the model. When an LLM guesses a number by trying to understand the document, it might be right, or it might be wrong. It has no way to know. When it writes regex.match() and the computer returns ['$2,340,000'], that result is a hard fact. What the model needs to understand is how to form a query—a general task it's likely good at—instead of trying to solve a domain-specific problem it has no direct training on.

Allowing an LLM to write and run code directly on your system would obviously be a security nightmare, so the implementation uses isolated-vm to create a secure sandbox for it to play in. The model cannot hallucinate rm -rf / or curl a random URL. Having a sandbox also prevents infinite loops or memory leaks. And since the document is immutable, the model can read it but cannot alter the source truth.

The process works as follows:

- 1. The document is loaded into a secure, isolated Node.js environment as a read-only

contextvariable. - 2. The model is given exploration tools:

text_stats(),fuzzy_search(), andslice(). - 3. The Loop:

- • The model writes TypeScript to probe the text.

- • The Sandbox executes it and returns the output.

- • The model reads the result and refines its next step.

- 4. The loop iterates until the model has enough proven data to answer

FINAL("...").

The system can work entirely locally using something like Ollama with Qwen-Coder, or with hosted models like DeepSeek, which are much smarter by default. It also works as an MCP that you can plug in and let your agent use to solve problems.

Finally, I used Universal Tool Calling Protocol (UTCP) patterns from code-mode to generate strict TypeScript interfaces. This provides the LLM with a strict contract such as:

// The LLM sees exactly this signature in its system prompt

declare function fuzzy_search(query: string, limit?: number): Array<{

line: string;

lineNum: number;

score: number; // 0 to 1 confidence

}>;

One problem is that LLMs tend to be messy coders; they forget semicolons, use hallucinated imports, etc. The way around that is to add a self-healing layer. If the sandbox throws a syntax error, a lightweight intermediate step attempts to fix imports and syntax before re-running. This keeps the reasoning chain alive and minimizes round trips to the model.

As a demo to test out the concept, I made a document containing a bunch of scattered data, with 5 distinct sales figures hidden inside 4,700 characters of Lorem Ipsum filler and unrelated business jargon.

Predictably, feeding the text into a standard context window and asking for the total promptly resulted in a hallucinated total of $480,490. It just grabbed numbers that looked like currency from unrelated sections, mashed them together, and called it a day.

Running the same query through RLM was a completely different story. The model took 4 iterations to converge on the actual solution. Instead of trying to guess, it started writing code to explore the document. It first checked the file size:

const stats = text_stats();

console.log(`Document length: ${stats.length}, Lines: ${stats.lineCount}`);

Next, it used fuzzy search to locate relevant lines, ignoring the noise:

const matches = fuzzy_search("SALES_DATA");

console.log(matches);

// Output: [

// { line: "SALES_DATA_NORTH: $2,340,000", ... },

// { line: "SALES_DATA_SOUTH: $3,120,000", ... }

// ]

And finally, it wrote a regex to parse the strings into integers and summed them programmatically to get the correct result:

// ...regex parsing logic...

console.log("Calculated Total:", total); // Output: 13000000

Only after the code output confirmed the math did the model verify the answer.

The key difference is that the traditional approach asks the model "what does this document say," while the recursive coding approach asks it to "write a program to find out what this document says." The logic is now expressed using actual code, and the role of the LLM is to write the code and read the results as opposed to working with the document directly.

As with all things, there is a trade-off here: the RLM approach is slower since it takes multiple turns and can generate more tokens as a result. However, if the document you're working on is itself large, then you will actually save context tokens by not loading it directly.

MCP Integration

The project also includes an MCP (Model Context Protocol) server, making it available as a tool for coding agents like Crush. Once configured, you can ask the agent to analyze documents that would otherwise exceed its context window or require precise data extraction.

The server exposes an analyze_document tool that takes a query and file path. The tool can then use the RLM approach to explore documents by writing code, executing it in the sandbox, and iterating until it finds the answer.

This creates an interesting dynamic where you agent writes the high-level query, the RLM's backing model (which can be a local Ollama instance) does the iterative code exploration, and the verified results come back to your agent. The grounding problem is solved at the tool level, so the agent can trust the results it receives.

The implementation is available at https://github.com/yogthos/Matryoshka.